USAGM Watch Commentary

By Ted Lipien

Following reports that due to multiple security violations the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) revoked a few years ago the authority of the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM) to conduct background investigations in hiring new employees, including journalists working for the Voice of America (VOA), and information that former heads of USAGM and VOA ignored for many months warnings about former Russian state media journalists with a history of anti-U.S. propaganda doing work for VOA, I reviewed some of the available archival records showing the Soviet influence operations at the Voice of America and its parent agency, the Office of War Information (OWI), during World War II.

These records in the National Archives and Presidential Libraries provide considerable evidence that the Soviet intelligence service had recruited spies who found employment at the Voice of America during World War II. However, most of the damage to VOA’s audiences in East-Central Europe, affecting tens of millions of people in the countries VOA helped President Roosevelt deliver to Stalin, and the damage to VOA’s journalistic mission, were done during the war and for a few years after the war not by Soviet spies but mostly by government officials occupying high level positions. Responsible for setting aside the principles of objective journalism and America’s liberal values for a utopian and mistaken view of communist Russia were the witting and unwitting Soviet agents of influence among the Voice of America’s extreme left-leaning leaders, editors, and broadcasters who were profoundly influenced by the communist ideology and easily blinded by the Kremlin’s propaganda — just as today, some extreme right-leaning private media figures in the United States and abroad are advancing Vladimir Putin’s recycled Soviet propaganda narrative to the American public. In both cases, they volunteered to be Russia’s agents of influence.

There were many Soviet agents of influence at the wartime Voice of America but only several actual Soviet spies. One of the Soviet agents of influence was the man somewhat mistakenly regarded as the first Voice of America director. Information from previously classified U.S. government documents about John Houseman has been available online for several years but never acknowledged by the VOA management. He was quietly forced by the Roosevelt administration to resign from his position for hiring pro-Soviet communists. The State Department, with support from the U.S. military intelligence and Supreme Allied Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, refused to give Houseman a U.S. passport for official VOA travel abroad, thus forcing him to resign.

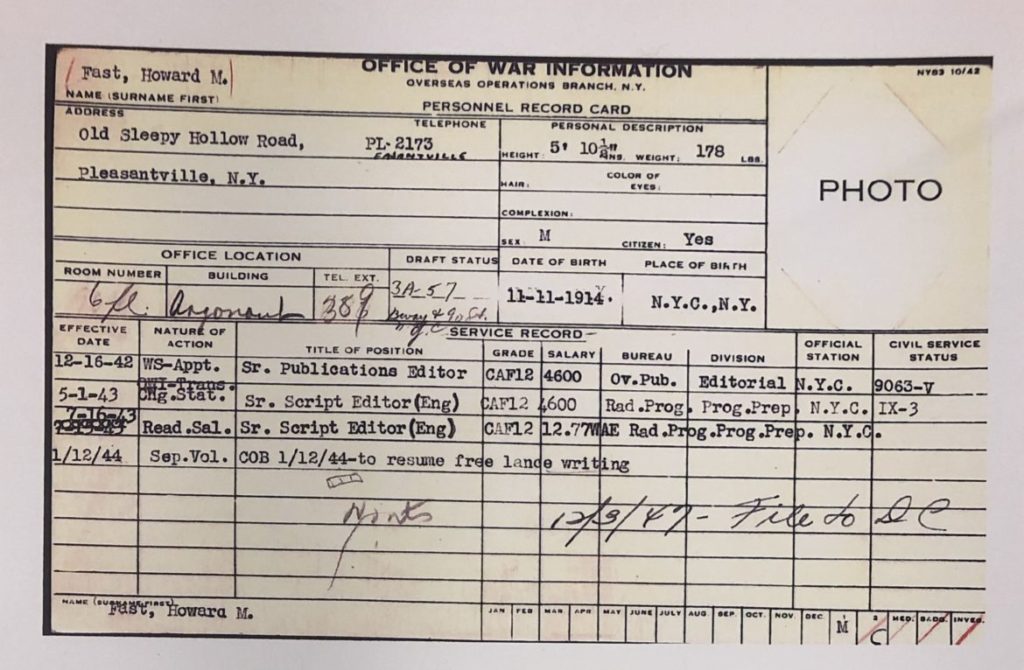

The Roosevelt administration used the same approach to force the resignation of VOA’s first chief news writer and editor, Howard Fast, who joined the Communist Party USA while still working for VOA and in 1953 received the Stalin Peace Prize. He was another important Soviet agent of influence at the Voice of America. I discuss VOA’s agents of influence more extensively in my article, “A Stalin Peace Prize Laureate Still Waiting for Acknowledgement of His Soviet Agent of Influence Role at Voice of America,” on the Cold War Radio Museum website.

While the Roosevelt administration was not at all opposed to pro-Soviet propaganda in support of the joint American-Soviet war effort against Nazi Germany, even some of the most progressive administration officials in the State Department and in the White House, with the exception of those who were secretly Soviet spies, did not want government employees who could be unduly influenced by a foreign nation, especially if they were Communist Party members.

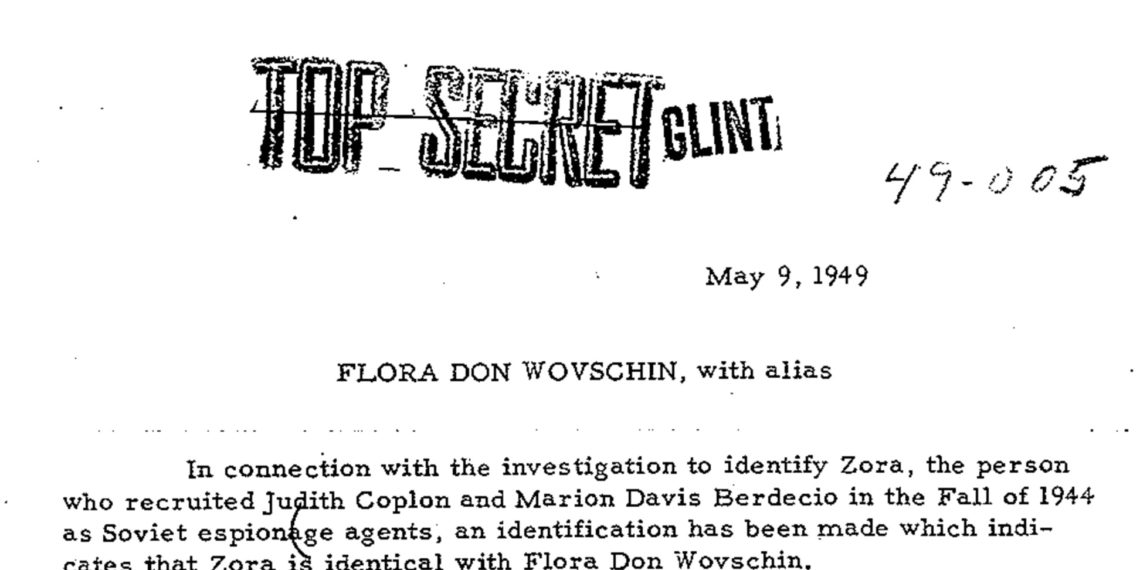

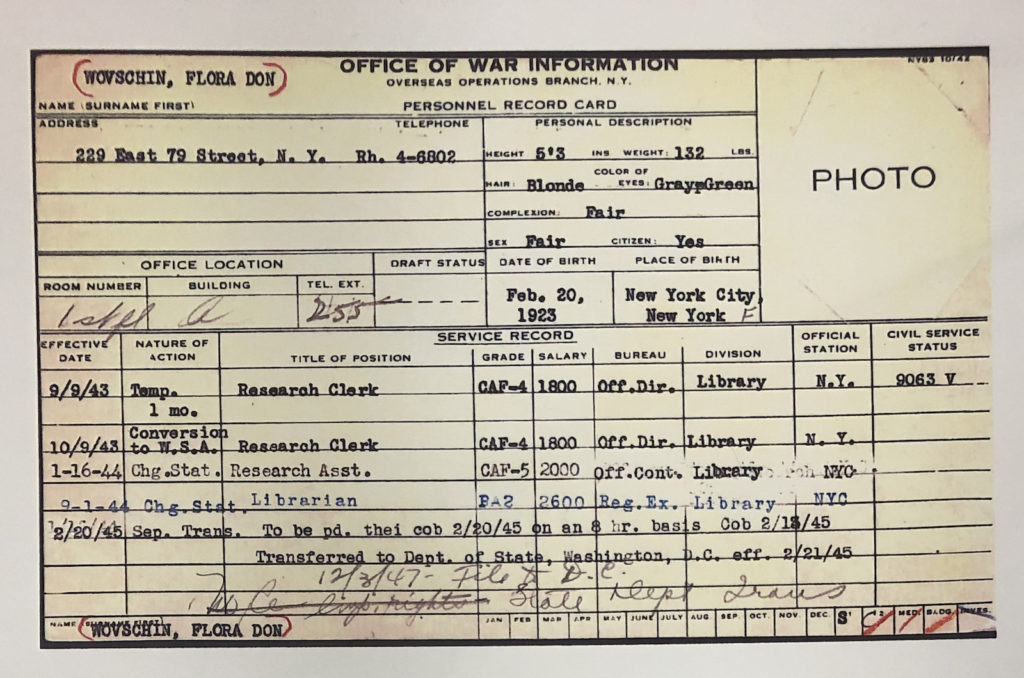

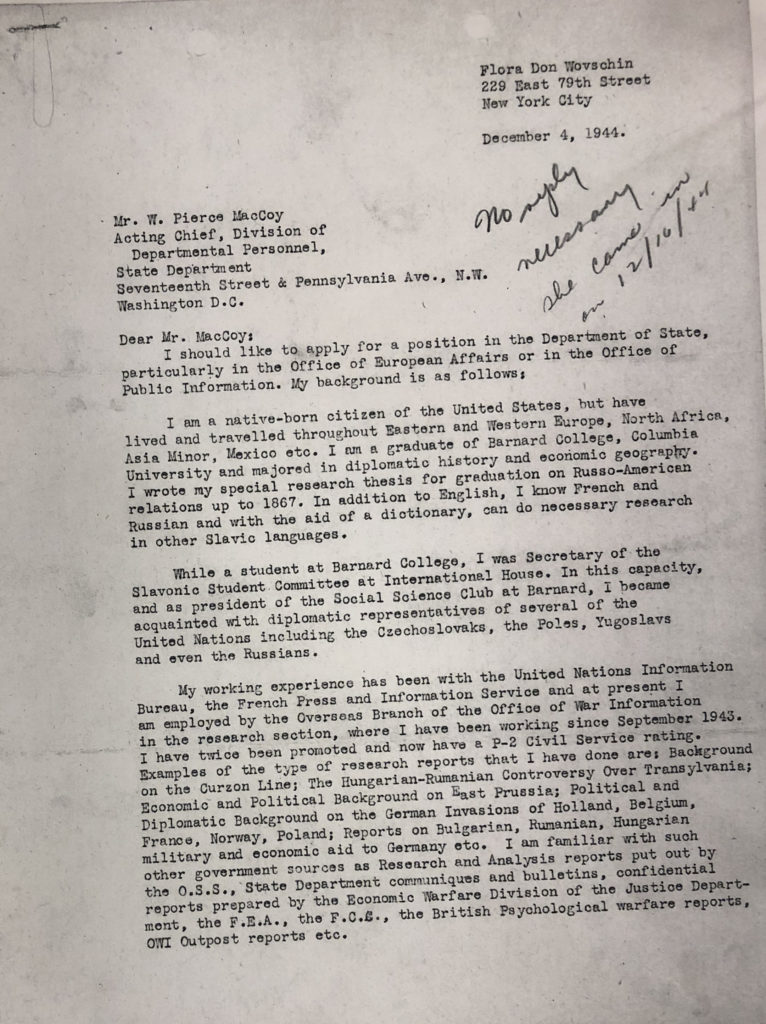

This article is mostly about Soviet spies, who were low-level OWI and VOA employees. It includes some never before mentioned information about Flora Don Wovschin (KGB codename ZORA), which I recently discovered. I also found a revealing quote from an ex-Communist who turned anti-communist. In his communist years, Oliver Carlson was a founder of the Young Communist League of America and lecturer at the University of Chicago. Carlson wrote in 1947: “The idea officially projected through such organizations as the O.W.I., was to cure ‘misunderstanding’ of Soviet Russia, which was suddenly discovered to be a ‘democracy’ and a noble social experiment.”

As an undergraduate student at Barnard College, Flora Wovschin vehemently defended the Kremlin’s line and strongly opposed U.S. military aid to Great Britain in early 1941 when Hitler’s Nazi Germany and Stalin’s communist Soviet Russia were still allies. She perfectly fit the description of an American idealist duped by propaganda and would change her views as demanded by the Communist Party. Her mother and her stepfather were also identified as KGB contacts. Flora Wovschin started working for the Office of War Information (OWI), which oversaw Voice of America broadcasts, in September 1943.

During World War II, members of Congress of both parties began issuing warnings about Soviet influence at the Office of War Information. These warnings intensified after the war and continued until the Truman administration, under pressure from Congress and the media, carried out management, personnel, and security reforms at VOA in the late 1940s and the 1950s. The Democratic Truman administration implemented most of these reforms before Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) started making his mostly false accusations and conducted his destructive hunt for Communists in the U.S. government, almost all of whom were already gone.

However, foreign propaganda influence and ideological and partisan activism at the Voice of America during World War II and, to a lesser extent, for a few years after the war were real. Disturbingly, the problem seems to have returned in recent years at the Voice of America, and it now includes interference not only by Russia but also China and Iran. In another recent development shedding light on the current crisis in the U.S. government-funded media outreach, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) found that Voice of America’s annual Program Review process lacked written action plans and written procedures for addressing lapses in journalistic standards, thus making it difficult to assess VOA programs for evidence of bias and foreign propaganda.

“Pro-Putin bias” on VOA Russian Service website was identified already in a 2011 study conducted by an independent Russian journalist and new media scholar. The study was commissioned by the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) — the former name of the U.S. Agency for Global Media.

Russian intelligence services may have been behind an incident in 2012, in which the VOA Russian Service was duped into posting a fake interview with Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny who is now one of Putin’s political prisoners in Russia.

Pro-Iranian regime bias in VOA programs was identified in 2018 by a BBG-commissioned study.

Pro-China bias, including charges that there were meetings between Chinese Embassy officials and Voice of America China Branch staff to evaluate VOA broadcasts, was described in a broader, independent study of the Beijing communist regime’s propaganda operations. The Report of the Working Group on Chinese Influence Activities in the United States, which highlighted some of the problems with VOA media outreach to China, was published jointly in October 2018 by the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and the Center on US-China Relations at Asia Society in New York.

Pro-government bias was also reported in VOA broadcasts to Ethiopia,1 and VOA broadcasting to Nigeria was tainted by an alleged bribery scandal resulting in more than a dozen VOA journalists being fired from their jobs in 2018.

Soviet Agent of Influence at VOA — Howard Fast (1953 Stalin Peace Prize)

During World War II, several Soviet spies worked at the Office of War Information, including the Voice of America’s foreign language services, but most of the Soviet propaganda and disinformation found its way into Voice of America wartime programs through the efforts of its most senior officials, editors, and writers, including Howard Fast who later became a Communist Party activist and in 1953 received the Stalin Peace Prize — the fact consistently hidden by the VOA management.

When asked whether he knew that American novelist Howard Fast, the first Voice of America chief news writer and editor, became a Communist Party USA activist and received the 1953 Stalin Peace Prize, Sanford Ungar, former VOA Director who served during the Clinton administration and is now the Director of the Free Speech Project at Georgetown University, said in an online panel discussion in February 2022 that this was a “McCarthyite question.”

His remark did not stifle the discussion, in which Ungar later mentioned a New York Times reporter and a Pulitzer Prize winner, Walter Duranty. The latter, among the Western journalists in Russia, was the most famous denier of Stalin’s crimes, including the Holodomor deaths of several million Ukrainians from forced starvation. Ungar also somewhat reluctantly agreed that Fast’s communist ties were true, adding that Fast was duped by the Soviets and later broke with Communism. But, in addition to Fast, there were many other Walter Durantys at the Voice of America in its early years, some in more senior and many in lower-level broadcasting positions — one of many embarrassing facts the organization’s management has tried to hide for many decades.

Although Ungar argued that Fast was later repentant over his support for Stalinist Russia, in reality, he was not. Although Fast publicly announced on February 4, 1957 that he had left the Communist Party, he never admitted that his advocacy in VOA programs for Soviet influence in Eastern Europe under Stalin did anyone in Eastern Europe and elsewhere any harm. He did not apologize for censoring news at the Voice of America or for his pro-Kremlin propaganda in the later period in his articles written even after Stalin’s death when Fast worked for the party’s newspaper, the Daily Worker. In his 1957 book, The Naked God, in which he announced his break with the Communist Party, Fast condemned mainly the party apparatus. He also condemned Stalin and his crimes, but he did not denounce Marxism or Communism as inhuman and violent ideologies — something many other disillusioned Communists did. Fast mentioned the Voice of America briefly in The Naked God but not in connection with his wartime VOA work, which he did not reveal in the book. He included much more information about his work for VOA but only later, in his memoir, Being Red, published in 1990. His references to VOA were largely dismissive and condescending.

In the panel discussion to commemorate the Voice of America’s 80th anniversary, Ungar said that there was nothing to suspect there were communist agents at VOA. He was mistaken.

As a Professor of History at Emory University, Harvey Klehr, and a Library of Congress historian, John Earl Haynes, showed in their book, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America (Yale University Press, 2000), secret Soviet intelligence messages monitored by the U.S. counterintelligence services as part of the Venona project contained “the unidentified cover names of several Soviet espionage contacts in the Office of War Information,” including one in the OWI French section.2

The Office of War Information was the wartime government agency in charge of the Voice of America language services and broadcasts from 1942 to 1945. They were part of the OWI’s Overseas Operations Branch in New York City.

Soviet Spy at OWI and VOA — Flora Wovschin (ZORA)

The Venona cables show that the KGB used an agent, codename “Philosopher” (OWI French section), for “providing background information and character appraisals – of OWI personnel.” The Venona project also revealed Flora Don Wovschin (codename “ZORA”), born in 1923 in the United States to Russian immigrant parents, as the most active Soviet agent in the Office of War Information, where she worked in New York as a research assistant and librarian during World War II in the Overseas Branch producing Voice of America broadcasts.

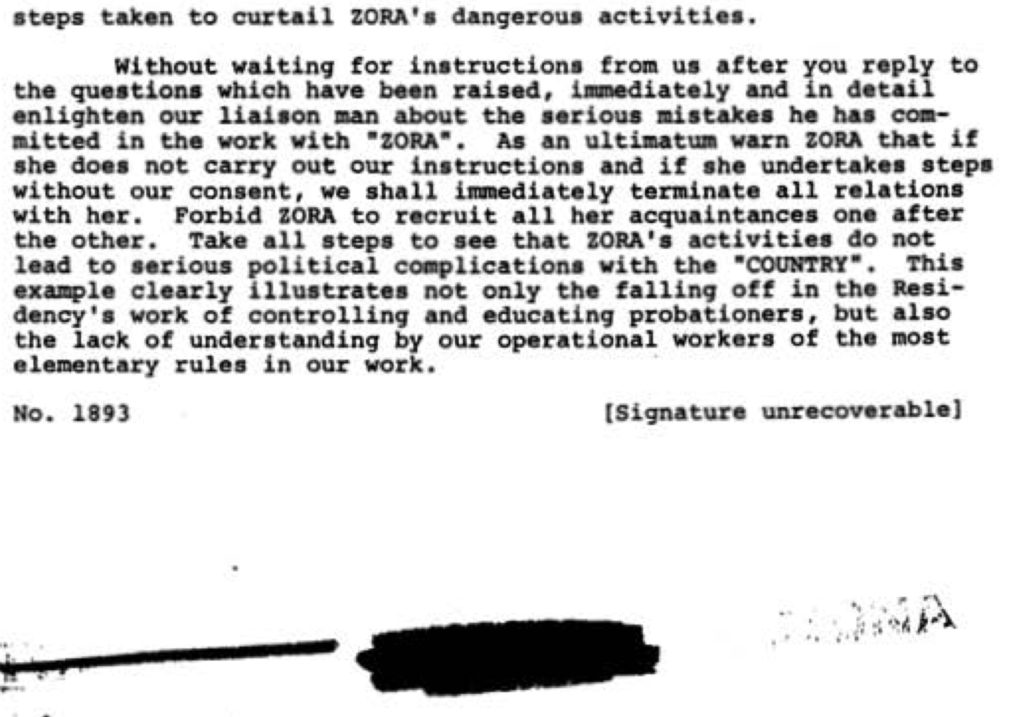

Flora Wovschin may have been the most active Soviet spy at the Office of War Information and the Voice of America, but she was not the most important Soviet agent of influence. The Kremlin’s most important agents of influence, although not necessarily the recruited ones, were some of the top OWI and VOA leaders and editors like Howard Fast, although Wovschin may have been able to influence them through her programming research. Wovschin recruited at least two or three other agents outside the OWI, including a Barnard College fellow graduate, Judith Coplon, who became a valuable KGB asset. She continued to impress the KGB with her productivity, but later the headquarters in Moscow concluded that she was becoming careless, violated KGB security rules, and was initiating too many risky contacts. At one point, the KGB threatened to break contact with her if she did not curtail her spy recruiting activities.

Flora Wovschin’s immigrant family seemed to be well off financially in America. Her father, Dr. William A. Wovschin, was a captain in the U.S. Army during World War I. Both her mother, Maria Wicher (cover name DASHA), and her stepfather, Enos Regnert Wicher (cover name KEEN), were Communist Party USA activists and appear in deciphered Venona messages as KGB contacts. Enos Wicher, who worked for the Wave Propagation Group of Columbia University’s Division of War Research, provided information on American military electronics.3

Flora Wovschin graduated from Barnard College and also studied at the University of Wisconsin School of Journalism. She is listed as WOVSCHIN, FLORA RHODA” in the Barnard College Mortarboard 1942 Senior Yearbook roster on page 190, and on page 160 as a member of the French Club. In February 1941, when Stalin and Hitler were still allies, she strongly opposed U.S. aid to Britain, following closely the Soviet and Communist Party USA propaganda line at that time. The Barnard Bulletin student newspaper issue of February 21, 1941, four months before Germany’s sudden attack on its former Soviet ally, quotes her as saying in a student debate that President Roosevelt’s Lend-Lease Bill to allow the transfer of U.S. arms to Great Britain has the support of “warmongers” in the U.S.

Flora Wovschin claimed that Hitler’s plan of “presenting a lie so monstrous that the people are confused” in attempting to propagandize a false doctrine, is being used by warmongers in the U.S. today. She dismissed as absurd the slogan popularized by press and radio that “Aid to Britain is the way to keep America out of war.” The Lease-Lend Bill (sic), said the speaker, has the support of crooked political machines and industrialists, such as munitions makers, who have profited enormously by the war so far.4

Interestingly, some of the positions taken by the American Student Union, which Flora Woschin represented at the debate, with the exception at that time with regard to support for Britain, were quite similar to the Office of War Information pro-Soviet propaganda in the later phases of the war. The article said that the ASU “proposes the cooperation of this country with existing non-belligerents, the strongest of whom is the Soviet Union, towards the strengthening of democracy and the promotion of the ‘people’s peace’ and the setting up of ‘people’s governments’ in the nation’s now at war.” The Lend-Lease Act was enacted on March 11, 1941, and eventually benefitted the Soviet Union after Germany attacked its former Soviet ally on June 22, 1941. Nazi Germany’s attack on the Soviet Union led to an immediate change in the Soviet and Communist Party USA propaganda line with regard to U.S. aid to Britain and to Russia.

In 1942, Flora Wovschin was elected president of the newly-formed Social Science Club at her college. The October 1, 1942 issue of Barnard Bulletin student newspaper has her front-page article about an interview she conducted with a Soviet student leader, Nikolai Krasavchenko, who was invited to visit the United States. The article is titled, “Soviet Student Leader Describes His Country’s War Against Nazism: Nikolai Krasavchenko, interviewed by Bulletin, Tells of Nazi Horrors, Studen Heroism.”5 The Barnard College Alumnae Magazine reported in October 1944 that “Flora Wovschin works with the O.W.I. in the Overseas Branch in New York. She is in the research section….” The March 1956 Barnard College Alumnae Magazine reports her as “Lost,” whereabouts unknown. In 1984, the Class of ’43 editor was still seeking information about Flora Wovschin.

Wovschin’s Office of War Information records stored at the National Personnel Records Center of the National Archives in St. Louis, MO. show that she “wrote research reports for the various units of OWI Overseas Branch, for Basic News, Military Desk, Publications, etc.” They included: “Background on the Curzon Line; The Hungarian-Rumanian Controversy Over Transylvania; Economic and Political Background on East Prussia; Political and Diplomatic Background on the German Invasions of Holland, Belgium, France, Norway, Poland; Reports on Bulgarian, Rumanian, Hungarian; Military and Economic aid to Germany.”

She was fluent in French, spoke Russian, and could use any of the Slavic languages. In 1945, she transferred from the OWI to the State Department, where she worked in the International Information Division as a divisional assistant until September 1945. According to a Venona cable dated “28 March 1945,” she was given by another Soviet spy within the U.S. government “the task of trying to get in the RADIO STATION [RATsIYa] about Swiss-German financial operations.” “RATsIYa” was the code name for the Office of War Information, including the Voice of America.

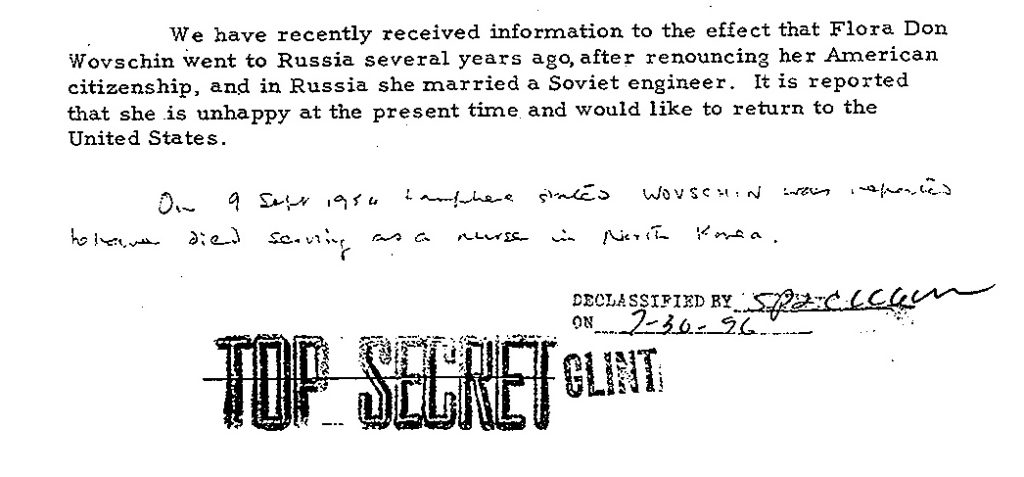

When, after the war, the FBI started efforts to identify her and find her, Wovschin fled in 1946 or 1947 to the Soviet Union, where she renounced her American citizenship and married a Russian engineer. The FBI received information that Wovschin later had gone to North Korea to work as a nurse and had died there.6

A message to Moscow from Communist Party USA leaders, marked “TOP SECRET” – Document 74 – found by Western scholars in the Soviet archives in the 1990s, leaves no doubt that the Soviet intelligence service also had other spies in the information departments of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which later became the Office of War Information. They included some who worked in the Voice of America foreign language services.

Document 74

Ryan to Dimitrov, enclosed in Fitin to Dimitrov, 1 June 1942, RTsKhIDNI 495-74-484. Original in Russian. TOP SECRET…

We are in contact with the department of foreign propaganda and with the information coordinator of the US. That department is one of the three departments in the so-called Donovan Committee and is directly controlled by the White House. We also have several persons working in the Czech and Italian radio-broadcast sections, although not in the overall program. We consider it expedient to prolong that contact and keep these persons in the radio-broadcast section, if, of course, you are in agreement.7

Ryan was Eugene Dennis, a Comintern agent in the United States who became general secretary of the Communist Party USA in 1945 and led the party until 1959. Pavel Mikhailovich Fitin was the head of the foreign intelligence directorate of the NKVD from 1940 to 1946. Georgi Dimitrov, a Bulgarian Communist, was the head of the Comintern until its dissolution in 1943.

Another document in the Comintern archives, a year-end report on the 1942 Communist Party activities and financing of an espionage network refers to another agent, Saito, “hired by the O.W.I. (Office of War Information) which is the government department of propaganda which among other functions prepares radio broadcasts to Japan and similar propaganda materials for Axis countries and occupied countries.” The Communist Party USA report to Moscow also stated that “There are reliable Chinese comrades and others who have been invited by O.W.I. for such work.”8

Soviet Agents of Influence at VOA — Anti-Communist Journalists Who Exposed Them

However, what the KGB and intelligence services of other communist nations wanted at VOA were not necessarily spies but witting or unwitting agents of influence. Soviet agents of influence at the OWI and the Voice of America during the war were far more numerous and much more valuable to the Kremlin than actual intelligence operatives. Some of the agents of influence occupied the most senior management positions, made critical programming decisions, and had access to President Roosevelt and other top U.S. government officials. A few of them were known to have had frequent contacts with individuals who were later identified as active Soviet spies or important agents of influence outside of the OWI and the Voice of America. It is through them that the Soviet intelligence services were able to convince President Roosevelt and some pro-Soviet State Department diplomats that Stalin had become a friend of democracy and would respect the right of religious believers. As Julius Epstein, a former OWI German desk editor, and internationally-published journalist who escaped from Nazi Europe, wrote in 1950, the Voice of America was engaged in promoting “Love for Stalin.”

There are still too many of the old OWI [Office of War Information] employees working for the Voice, both in this country and overseas. I mean those writers, translators and broadcasters who so wholeheartedly and enthusiastically tried for many years to create ‘love for Stalin,’ when this was the official policy of our ill-advised wartime Government and of our military government in Germany. There is no doubt that all those employees were at that time deeply convinced of the absolute correctness of that pro-Stalinist propaganda. How can we expect them to do the exact opposite now?9

Epstein, who was sympathetic to Communism in his youth and briefly joined the Communist Party in Germany before becoming an anti-communist, realized that extreme pro-Stalin propagandists were an influential group in the U.S. agency that started producing Voice of America broadcasts during the war.

When I, in 1942, entered the services of what was then the “Coordinator of Information,” which became after a few months the O.W.I., I was immediately struck by the fact that the German desk was almost completely seized by extreme left-wingers who indulged in a purely and exaggerated pro-Stalinist propaganda.10

Epstein, a Jewish refugee in America with liberal, pro-socialist views who escaped the Holocaust and published anti-Nazi articles in European and American newspapers and magazines, hardly fit the description of a white supremacist critic of U.S. government broadcasts. Another former -ex-Communist who turned anti-communist and exposed Soviet influence at the Office of War Information was Oliver Carlson, an American writer, journalist, founder of the Young Communist League of America, and lecturer at the University of Chicago. His description of pro-Soviet propaganda by the OWI was similar to Julius Epstein’s observations.

During the War Years — and largely with government blessing — the Communists moved en masse on the radio, as they did on the movies and the press to help “sell” the American people on the virtues of our Soviet ally. The idea officially projected through such organizations as the O.W.I., was to cure “misunderstanding” of Soviet Russia, which was suddenly discovered to be a “democracy” and a noble social experiment.11

Carlson knew that the Office of War information produced such propaganda not only for overseas audiences through the Voice of America but also for domestic audiences in the United States until Congress eliminated most of its domestic propaganda budget in 1943. Carlson wrote about domestic OWI propaganda programs, which were essentially the same as VOA programs.

Tens of millions of radio listeners were deluged with streamlined and dramatic presentations to prove that any talk of Russia as a ruthless dictatorship was a “reactionary plot, The Bolshevik regime, it turned out, was just a Russian version of our own War for Independence, Lenin a Russian replica of George Washington, Stalin a compendium of Jefferson, Jackson and Lincoln.12

Carlson noted, however, in his 1947 pamphlet, Radio in the Red, published by the Catholic Information Society, that “such crude propaganda, now that the war is over, has declined.”13

A Polish Spy at VOA in Munich

After the war, when the number of Soviet agents of influence at the Voice of America indeed greatly diminished, a communist spy, Zbigniew Brydak, aka Stefan Michalski, got a job at the VOA bureau in Munich in the early 1950s before going back to Poland and launching attacks on VOA and Radio Free Europe and their new anti-communist broadcasters.

Brydak was a particularly dangerous agent provocateur. Before he arrived in the West, he entrapped and denounced to the communist secret police young members of the pre-war Polish scouting movement and its wartime underground anti-Nazi resistance units. According to my former VOA Polish Service deputy chief, Marek Walicki, who knew Brydak, some of these young men may have been tortured and executed as a result of Brydak’s denunciations.14

By the time Brydak appeared in the West, the Voice of America was already reformed, its Soviet sympathizers dismissed, and a newly-hired group of refugee journalists engaged in countering Soviet propaganda as part of President Truman’s “Campaign of Truth.”15

One of the most important initiatives of Truman’s presidency was the launching of Radio Free Europe (RFE). Brydak tried to get a job at RFE but was rebuffed. RFE, and Radio Liberty (RL), which broadcast to the Soviet Union, had in later years several communist agents working for them, usually in minor positions without significant editorial influence. Communist regimes perceived the two stations as much more dangerous for their grip on power and concentrated their spying activities on them rather than on VOA.

Soviet Agents of Influence Among Senior Leaders

Among Soviet agents of influence, Howard Fast was hardly alone in helping to spread the Soviet disinformation about the Katyn massacre and other Soviet propaganda lies in the Voice of America and the Office of War Information programs. All the individuals, later presented by their admirers as the “founding fathers” of the Voice of America, participated in promoting the Katyn lie: OWI Director Elmer Davis, his deputy and FDR’s speechwriter, Robert E. Sherwood, Joseph Fels Barnes, Wallace Carroll, and John Houseman, the theatre producer and actor later declared to be the first Voice of America director. They helped to deliver Eastern Europe to Stalin but never apologized for it and were later acclaimed as the defenders of truth in journalism. Still, they were all profoundly naive about Soviet Russia, Communism, and Joseph Stalin. As late as 1948, Wallace Carroll defended the Kremlin’s lie about the NKVD’s Katyn massacre of thousands of Polish military officers who were prisoners of war.

Houseman and Fast were forced out from VOA by the liberal and progressive Roosevelt administration — the fact also hidden by the Voice of America management. Most of the other Soviet and communist agents of influence were dismissed during the Truman administration, which also tightened the security clearance process and hired many anti-communist refugee journalists from Eastern Europe. They helped to save the Voice of America’s reputation. However, they were still subject to programming restrictions and anti-immigrant discrimination from the VOA and agency management until the Reagan administration allowed full, uncensored reporting on Soviet and other communist atrocities.

- Nick Turse, Propaganda Machine: Voice of America Is Accused of Ignoring Government Atrocities in Ethiopia,” The Intercept, May 21, 2021, https://theintercept.com/2021/05/21/voice-of-america-ethiopia-bias/.

- John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America, Yale Nota Bene (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2000), pp. 197-199.

- John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America, Yale Nota Bene (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2000), p. 198.

- Barnard Bulletin, Opposing Views Debate U.S. Policy: ASU, WAW Proponents Discuss Aspects of Assistance to Britain, Vol. XLV, No. 25, February 21, 1941, pp. 1 and 3, https://digitalcollections.barnard.edu/object/bulletin-19410221/barnard-bulletin-february-21-1941.

- Flora Don Wovschin, “Soviet Student Leader Describes His Country’s War Against Nazism: Nikolai Krasavchenko, interviewed by Bulletin, Tells of Nazi Horrors, Studen Heroism,” Barnard Bulletin, Vol. XLVII, No. 2, October 1, 1942, https://digitalcollections.barnard.edu/object/bulletin-19421001/barnard-bulletin-october-1-1942.

- Haynes and Klehr, Venona, pp. 200-2001.

- Harvey Klehr, John Earl Haynes, and Fridrikh Igorevich Firsov, The Secret World of American Communism (New Haven and London: Yale University Press), pp. 272-273.

- Klehr, Haynes, and Firsov, The Secret World of American Communism, pp. 210-211.

- Journalist Julius Epstein quoted by Congressman George A. Dondero (R-MI) in Congressional Record, August 9, 1950. The quote was from the article which was published in the Evening Star Washington newspaper on August 7, 1950. Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 81st Congress, Second Session, Appendix. Part 17 ed. Vol. 96. August 4, 1950, to September 22, 1950. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1950, pp. A5744-A5745.

- Julius Epstein, “The O.W.I. and the Voice of America,” a reprint from the Polish American Journal, Scranton, Pennsylvania, 1952.

- Oliver Carlson, Radio in the Red (New York: Catholic Information Society, 1947), p. 7.

- Carlson, Radio in the Red, p. 7.

- Carlson, Radio in the Red, p. 7.

- Paweł Machcewicz, Poland’s War on Radio Free Europe, 1950-1989 (Washington, D.C : Stanford, California: Woodrow Wilson Center Press ; Stanford University Press, 2014), pp. 70-75. Also see: Marek Walicki, Z Polski Ludowej do Wolnej Europy (Warszawa: Bellona Spółka Akcyjna, 2018), pp. 170-182.

- Ted Lipien, “President Truman Launches Voice Of America Transmitter Ship ‘Courier’ – Cold War Radio Museum,” accessed November 4, 2022, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/timeline/president-truman-launches-voice-of-america-transmitter-ship-courier/.